White Goddess is the title of Chapter 21 of Drug Lord, and it is about Pablo Acosta’s addiction to crack cocaine, an addiction that he was unable to shake off and that contributed to his downfall.

Pablo Acosta had been using cocaine off and on for some time, but until 1984 he had only snorted it. Though he was by then a big-league marijuana and heroin trafficker, even he at times had trouble getting enough cocaine for personal use. In desperation, he would call Sammy Garcia from Ojinaga with a coded message that his help was needed. “Traeme dos novias vestidas de blanco—Bring me a couple of brides dressed in white” was coded language instructing Sammy to bring two ounces of cocaine. Becky had her own source in El Paso, so getting Pablo what he wanted was never impossible provided he was willing to wait a few days.

In 1984, one of drug lord’s brothers introduced him to crack cocaine smoked a la mexicana—crack laced cigarettes. They were made by pulling out strands of tobacco from the end of an unfiltered cigarette, then using the empty end as a shovel to scoop up a fraction of a gram of powdered crack. After twisting the end into a wick and tapping the cigarette so that the powder settled into the tobacco, Pablo would pass a butane lighter underneath the cigarette to vaporize the powder and then take a long draw. Within seconds the drug was circulating in his brain, bringing with it the feelings of supra-humanity he had begun to crave.

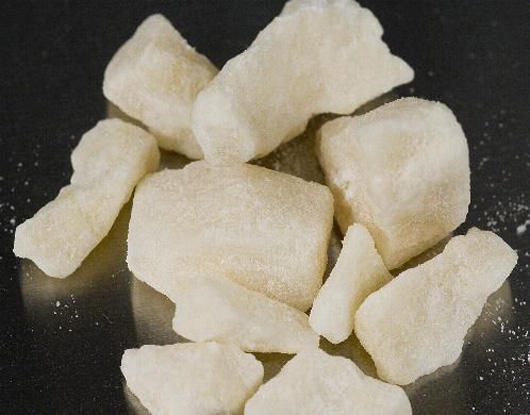

Cocaine hydrochloride, the drug produced by the Colombian drug organizations, has a high melting point and cannot be smoked easily. Cocaine stripped of the hydrochloride molecule, however, is easy to vaporize, and so it is smokable. “Cooking” cocaine, the traffickers’ expression for eliminating the hydrochloride from the formula and lowering its vaporization temperature, was a ritual Pedro Ramirez Acosta, Pablo’s inseparable nephew, carried out with the reverence of a priest consecrating bread and wine.

Pedro had two ways of preparing it. One was the crude way, melting a mixture of cocaine and baking soda together over a flame. Any big spoon and a sustained flame would do for small amounts, while any pot and an oven would do for preparing larger quantities. After melting his mixture, Pedro would scrape the solidified rock until all of it was reduced to fine, smokable powder. This was the technique Pablo and his entourage generally used to prepare crack, putting up with the impurities that were the disadvantage of the method.

The more sophisticated way consisted of dissolving baking soda in water, bringing it to a boil, then adding cocaine. As the solution cooled, the insoluble cocaine base floated to the top in an oily film and coalesced in the center. The impurities, meanwhile, remained in solution. When the coalescence solidified, Pedro would then mortar or scrape it into a fine powder.

It was the myrrh and incense of the traffickers’ credo.

Over time, Pablo became obsessed with anything having to do with the subject of cocaine and cocaine trafficking. Scarface, the film about a slick Marielito trafficker who eventually got rubbed out in Miami by a small army of Colombian gunmen, became a big hit in Pablo’s home on Calle Sexta. Not long after Becky Garcia first drove down to Ojinaga to work for Pablo, she was waiting with him at his brick house for people to arrive to discuss some deal that he had going.

“You wanna watch a movie?” Pablo asked.

“Sure, why not?”

Pablo slid a videocassette of Scarface into the VCR.

“I’ve been wanting to watch this one,” Becky said as she snuggled into the sofa.

“Oh, it’s great, great! Wait till you see it.”

Just about everybody in Pablo’s inner circle had seen it again and again. A group of Pablo’s people would be meeting somewhere, at Becky’s apartment, at the apartment up behind Malaquias Flores’ radio station, at Pablo’s brick home on Calle Sexta or at Pedro Ramirez Acosta’s home downtown. Pablo would send someone for a VCR and the videocassette and they would all sit around snorting cocaine or smoking crack while watching the De Palma flick.

Once, a few days after everyone had viewed Scarface for the umpteenth time, the small group of Pablo’s most intimate circle — Marco, Becky, Pedro and a couple of Marco’s brothers — were sitting around a table in Becky’s apartment on one of the side streets near the town square, weighing ounces of cocaine on a scale. In front of them were three or four pounds of cocaine in several plastic bags. One of the bags contained an entire kilo. Pablo picked it up and opened it. He rolled back the top and with a clever smile looked around the table. “Watch this!” he said. Mimicking Al Pacino in one of the more bizarre scenes of Scarface, Pablo let his head fall into the bag. When he raised it, there was cocaine all over his face—in his mustache, on his high Indian cheekbones, on his big nose, in his nostrils and all over his chin.

His gold-lined teeth sparkled through the powdery mask. “What’s left in life?” he asked.

It was not just the cocaine that drew him to the film. Pablo identified with the shootouts, the murder attempts, the trafficker’s rise to power, the bloody hits, the flash of dollars, the lavish living, the feeling of being number one.

He never watched Scarface from beginning to end, perhaps not really wanting to see how it all turned out. Instead he would tell Becky or someone else to rewind it or advance it to the parts of the movie he really wanted to see.

“You remember that part where …? It was just like when …”

The Scarface of the movie was Cuban, and Pablo talked about going to Cuba one day because the Cubans were into trafficking cocaine, too. Or to Colombia. But no, if he went to Colombia he would get too big, bigger than those “sons-a-beeches” he had begun warehousing and smuggling cocaine for, and somebody would try to kill him. It really did not matter how big the castle, just as long as you were king of it. Better just to stay in little old Ojinaga.

Here he was the lord.

Just how bad Pablo’s addiction had become was already evident by late 1985. He could go days on end — he had to — just to keep everything running: the drugs coming in, the buyers supplied, the authorities appeased, and his gunmen, runners, pilots, packagers, suppliers, pot-farm workers and intelligence sources paid. By snorting cocaine or smoking crack he could get by on an hour or two of sleep a day. He had girlfriends all over the place and kept some women lodged at the hotels and motels—a habit, along with the cocaine, that eventually alienated his wife. He would go to one of the rooms and just zonk out. Half an hour, an hour, two hours later he was back on his feet. But eventually the pace would catch up with him.

Marco and Becky knew how to recognize the symptoms. First he would start to forget things, important things, like a meeting in the afternoon that he had set up with somebody that very same morning. Or he would lose track of what he was saying, or suddenly switch subjects and start talking about how they blew away Fermin at El Salto, or how he and Pedro had machine-gunned that punk kid who tried to kill him at the intersection near Motel Ojinaga. His command of English would start to deteriorate, and even in Spanish he would not make sense.

“Huh? What did you say?” Marco or Becky would ask him, looking at each other.

On one occasion in the autumn of 1985, following one of these stressed out and coked out episodes, they drove Pablo downstream to the village of Santa Elena, his birthplace, to force him to dry out enough to start functioning again. They had driven to this out-of-the way adobe village numerous times for one reason or another, more often than not to smuggle drugs. This trip would be the last that Pablo, Marco and Becky would ever again make to Santa Elena together.

On previous trips, Pablo had usually been entertaining, talking knowledgeably about the history of the village and the region. But on this trip, he kept mumbling and rambling on like a drunk and his companions couldn’t make any sense out of what he was saying. It was driving them nuts. They had to take the uneven dirt road through San Carlos, then on to Providencia, then down the tricky mountain road from the top of the Sierra Ponce to the river, a long, bone-jarring drive. The only customized cigarettes they had were the ones Pablo brought with him in his shirt pocket. He always prepared an entire pack to smoke when he was on the road, but by the time they got to Santa Elena, the pack was all smoked and there was not any cocaine in the village.

That was why Marco and Becky were bringing him there—to dry him out.

They drove up in mid-afternoon in front of Pablo’s adobe, about a hundred yards from the Rio Grande, followed by the gunmen. The gunmen who had followed in another vehicle went to scout around the village and to take up their usual positions. Marco and Becky helped an unsteady Pablo inside. They sat him down on the edge of a bed in one of the small bedrooms inside the U-shaped building that was practically all bedrooms, with the living room, dining room and kitchen merged together in the front by the lack of partitioning walls. Pablo had fortified the adobe with heavy metal doors and window shutters thick enough to stop bullets. The doors had slits wide enough to stick the muzzle of a gun through. The walls were nearly two feet thick. The adobe housed an arsenal of semiautomatic and automatic weapons and a stockpile of ammunition. In other village homes were additional stockpiles of ammunition.

After they sat him down on the bed, Pablo asked for his gon. Marco and Becky had confiscated his rifle and pistols as a precaution. When he got superstoned Pablo frequently would get into a Wild West mood and shoot at walls or in the air like a drunken gunslinger. As he felt around his belt for his .45 and in his boot for the smaller pistol he usually kept there, he suddenly realized that he had been stripped of his weapons. Then he saw he was out of crack-laced cigarettes and that there wasn’t any cocaine to make more of the cigarettes with. Like a true addict, he started throwing a tantrum:

“You dumb motherfuckers!” Pablo screamed. “Let’s go, let’s go get some. I know where to go. Come on, let’s go get some.” He ordered them to drive him all the way back to Ojinaga to get more cocaine.

“Okay, listen,” Marco said. “We’ll go back and get some if you take a nap. Lie down and rest for just a few minutes. And then we’ll go back, I promise.”

“All right, all right,” Pablo mumbled.

He lay down. Becky gave him some milk with ice. He drank it like a docile child. Soon he started drifting off, mumbling to himself. One of Marco’s brothers who had been sent to scout around the village came back to the adobe after making the rounds. Everything okay, everything tranquilo—quiet, he told Marco. The brother joined Marco and Becky at the kitchen table playing cards. Finally Pablo dozed off. They knew he would wake up in an hour or so without a tranquilizer, but Marco was prepared. He pulled a syringe from a carrying case and sat next to Pablo on the bed. It was a sedative he had gotten from a doctor in Ojinaga. Marco skillfully slid the needle into Pablo’s arm, taking care not to hurt him. Becky was always amazed at Marco’s tender side, given all the brutal things she had seen him do. After giving the injection, Marco pulled Pablo’s boots off, undressed him, and pulled a bed sheet up to his neck.

There was not much to do in an adobe village in one of the most isolated, inhospitable regions of North America. After tiring of cards, Marco and Becky walked around the village, then strolled down to the edge of the Rio Grande to watched the yellow-brown water flow by. On the American side, a good stone’s throw across, Becky could see a wide sandbar that ended where a jungle of tall mesquite and ancient cottonwoods began. The thick vegetation grew in the river floodplain for about half a mile inland. On the other side of the thicket, a two-lane asphalt road led up a hill to the U.S. ranger station. The station, its American flag flapping above, was visible from Santa Elena.

Marco sent someone across in a rowboat to buy up all the cigarettes at the park store. The villagers used the boat to ferry back and forth across the Rio Grande. Some with border-crossing cards even kept their pickup trucks on the American side. Using the highways on the American side, they could drive to Presidio and cross over to Ojinaga in less than two hours, whereas on the Mexican side it was a grueling six- or seven-hour ride up through the mountains over the crude roads Marco and Becky had used earlier that day.

As they sat there watching the swirling water, Marco and Becky were reminded of the history of the village Pablo had told them during previous stays there. Pablo had always loved the primitive Santa Elena valley, hemmed in on one side by the river, on the other by the escarpments of the Sierra Ponce. He liked to boast about the exploits of his father when he smuggled candelilla wax with Macario Vazquez, the most famous of all the wax smugglers, and about their shootout with the forestales in the hills above Santa Elena. Or he would get historical and talk about the successive waves of settlers who cleared the land and worked it against all the odds.

Pablo had heard the pioneer stories from his father and aunts and uncles: how settlers had originally come in the 1930s from the Juarez agricultural valley to create an edido — a communal farm — at Santa Elena, but the farming venture failed and most of the settlers headed north. Policarpo Alonzo, one of the original settlers, set out to establish another edido at Santa Elena in 1950 by recruiting sixty families from the Juarez area. They obtained communal title to the land, a loan from the rural bank to buy seed, fertilizer, picks, shovels, tractors and a pump to draw water from the river. In the beginning, while waiting for the loan money, they had little food and went into the mountains to hunt wild burros they killed by chasing over cliffs or by cornering in box canyons and clubbing to death. In the first year, Pablo recounted, the settlers were able to clear seventy hectares of boulders and tenacious mesquite roots where they planted cotton to repay the rural bank. As usual, some of the men worked more than others, some not at all, even though the loan money and the land had to be divided up in equal shares. Pablo described how the settlers made adobe bricks for their shelters and gathered ocotillo stalks for the roofing and felled cottonwoods for the beams. They erected adobes on what they thought was high ground, but at the first big rain the water cascaded off the top of the Sierra Ponce and turned the nascent village into a depressing muck bath. Then in 1958, the Rio Grande flooded and wiped out much of the labor of eight years. Many of the families saw that there was not any future for them in Santa Elena, working land that could never really be theirs: Both nature and a government claimed it. They eventually migrated north.

The stories about communal Santa Elena usually went over Becky’s head. How do you explain an edido to an American? But Marco understood.

Get this classic book about Pablo Acosta from Amazon.com

Much later, Pablo and his gunmen would sometimes run into some of the people he had known back in those early days of poverty and struggle. They would cross paths on the dusty road between San Carlos and Ojinaga, or in one of the sun-baked mud villages here or there in the desert. Some of these former acquaintances had been caught up in evangelical movements and went about the desert preaching la palabra de Dios—the word of God. They would give Pablo a copy of the New Testament printed in large type. These old acquaintances now had the pushy insistence of converts, but Pablo was troubled for another reason. One of these preachers would later tell about one of these desert encounters and how Pablo said to the preacher, earnestly, “Please pray for me,” and, “Don’t forget me in your prayers.”

The next morning Pablo woke with an excruciating headache. It was not caused only by the withdrawals. For the most part his headaches were the consequence of the many bullet wounds to his head. One bullet that had grazed him just above an eyebrow had somehow affected a nerve. That eyelid continually drooped, particularly when one of his headaches raged. He asked Becky for some aspirin and swallowed a handful. Still half-stoned, he was also groggy from the sedative. Marco fixed him breakfast, then cooked up another meal when he said he was still hungry. After that, Pablo smoked some regular cigarettes and went back to bed. He slept soundly for another twenty-four hours.

Marco and Becky had some business to take care of in Ojinaga. They drove back that day, leaving some of the pistoleros to watch over Pablo. When they came back the following morning, Pablo was already up and was showered, shaved and fresh looking. Instead of the stoned, irrational half-man of the last couple of days who had been ready to shoot up everything, here was the bright, intelligent and alert Pablo that Marco and Becky had always admired.

They were back in Ojinaga later that day and Pablo was back on top of the world, eager to start moving again.

Posted in

Posted in