This book came about because of the kidnapping of an American newspaper photographer by a Juarez drug trafficker, a brutal and unprecedented event that caused an international scandal and brought about the downfall of one of the major drug traffickers of the time.

Until the kidnapping, I didn’t have much interest in the subject of drugs. Drug trafficking was part of the background noise of the El Paso-Juarez region where I worked as a reporter. It was low keyed even in its violence; it did not draw too much attention to itself. My journalistic work, which had begun for the El Paso Herald-Post in 1984, focused primarily on reporting on a political movement in northern Mexico that was challenging the entrenched one-party system that had ruled Mexico since 1929. Juarez, the largest city in the state of Chihuahua, was the scene of what today would be called a “color” revolution — a democratic movement that used tactics of non-violent resistance to achieve its goals. Such a revolution was unfolding only ten blocks south of the newspaper, just on the other side of the Rio Grande.

The Rio Grande marks the border between the United States and Mexico and begins at El Paso and ends at the Gulf of Mexico.

Opposition political parties, which were able to mobilize tens of thousands of people for their rallies and protests, had serious gripes: Six decades of control by a single political party had resulted in a level of corruption throughout Mexico that was staggering for its severity. By some estimates, a third of all tax money ended up looted by politicians and bureaucrats through one kickback scheme or another, ensuring a continuation of the chronic poverty that plagued the country.

The political system kept itself going by allowing opposition parties to form and compete for power, but it rigged elections so that the official party candidate always won. The aim was to burn up the energy and resources of its opponents in fruitless campaigns, yet gain the appearance of democratic legitimacy by holding elections. The electoral fraud techniques were so finely tuned that elections could be engineered to whatever percentage the government party thought appropriate for a given race. The opposition movement, therefore, focused its efforts on breaking the cycle of electoral fraud by exposing its mechanisms, backed up by massive street demonstrations.

As I eventually came to understand, the corruption that pushed Mexican citizens to the streets in protest went far beyond the looting of the public treasury; it was much deeper and far more insidious, causing harm not only to the people of Mexico but to the citizens of all of North America. This dark face of Mexico involved not just collusion with organized crime, but actually encouraging and regulating it. It was a system of command and control that ran through the country like the arteries and veins of a body, with its heart in Mexico City.

It was against this background of state-sponsored crime and high political drama that the kidnapping occurred, an unintended consequence of a series of stories on organized crime the newspaper had published. The reports focusing primarily on organized crime enterprises on the American side of the Rio Grande, but since I was the Mexico reporter, I was asked to contribute a piece about such crime in Juarez. That meant drug trafficking. When I first began my work in Juarez, several Mexican journalists had cautioned me that if I wanted to stay out of trouble I should avoid three subjects: political corruption, police corruption, and drug trafficking. Ignoring the advice, I wrote a story about a fancy nine-story hotel a Juarez drug trafficker was building on one of the main boulevards. The story was published and was picked up by a wire service.

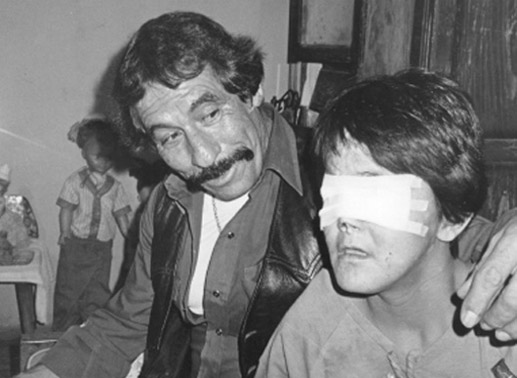

Juarez drug trafficker Gilberto Ontiveros

A few days later, someone from faraway Seattle called and said the Seattle Times wanted to print the story, but needed a photograph of the hotel. The newspaper sent a freelance photographer, Al Gutierrez. As it turned out, the photographer did not know what he was getting himself into. The newspaper assumed he had read the hotel story and would take appropriate precautions. But he had not read it and treated the job like any other assignment. He took photographs from the street, then asked permission to photograph inside the construction site. He ended up being brought to the very drug trafficker who had been exposed in the story, Gilberto Ontiveros, and the hapless photographer realized only too late he was now a prisoner just several miles from the newspaper that had sent him. Ontiveros and his cronies subjected the photographer to a brutal interrogation: Was he really a newspaper photographer, or was he actually DEA? They beat him, threw him down a staircase, put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger, and threatened to rape him and scald him with boiling water if he didn’t tell them what they wanted to know.

If this kidnapping had occurred in the Juarez of today, the photographer would have been murdered and his body, “bearing signs of torture,” dumped on a street corner. But this savage action was intended as a warning to the American media to back off, and it needed a live messenger. Instead of killing Gutierrez, his kidnappers drove him out to the desert and dumped him — twelve hours after abducting him. Battered and frightened, he made his way back to El Paso, reaching the newsroom an hour before the morning editors arrived. He left a note about what had happened. The last line said, “And tell Poppa they’re going to kill him.”

To use a worn expression, the kidnapping was a wake up call. Drug traffickers really were the dangerous people that Mexican journalists claimed, and as I quickly learned, they operated with impunity through impenetrable arrangements with power. They could literally get away with murder.

The kidnapping and torture of the newspaper photographer, however, backfired. News organizations on both sides of the border closed ranks behind the Herald-Post, whose editors rose to the occasion through the use of aggressive journalism and savvy politicking. Among other actions, the editor in chief, Jay Ambrose, fired off letters of complaint to the governors of Texas and Chihuahua, to the presidents and attorney generals of both countries, and to Texas congressmen and senators.

For my part, I lodged a criminal complaint against Ontiveros with the state prosecutor in Juarez. Just as writing about these people could be dangerous, filing a criminal complaint against a drug trafficker was simply not done in Mexico. It invited reprisals. But it had to be done, if only for its symbolic value. Ontiveros had brutalized an innocent man and had threatened to take my life, all because of a newspaper story. It was a personal challenge, but more importantly, it was also a matter of free speech. Was the American media going to be intimidated into silence?

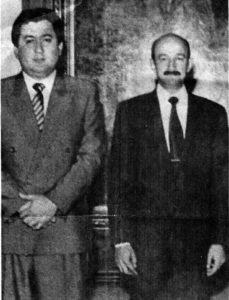

Mexican federal police commander Guillermo Gonzalez Calderoni (left) with Carlos Salinas de Gortari, president of Mexico from 1988 to 1994, in this undated photo.

As the pressures grew, it became impossible for Mexico to sweep the incident under the rug. Three days after the kidnapping, the Mexican government sent a team of agents headed by Comandante Guillermo Gonzalez Calderoni, an up-and-coming federal agent with solid political connections in Mexico City, to arrest Ontiveros.

My education about the true nature of the Mexican political system was just beginning. I was soon tipped off about the involvement of the Chihuahua state police in the theft of American automobiles. Someone showed me a bunch of vehicles — newer SUVs, trucks, sedans, all with American license plates — parked around the state police headquarters. My source said they had all been stolen from towns in New Mexico and Texas by gangs of car thieves who operated under the wing of the state police, which allowed their activities provided the thieves turn over a percentage of the stolen vehicles to the agency. State policemen, the very men who were responsible for investigating such crimes, drove them as if they were personal property. Many of these vehicles even ended up being driven by some of the Juarez journalists, who accepted them with the understanding they were not to expose police crimes.

With a newspaper photographer in tow, I staked out the police headquarters from a nearby balcony, and we got a slew of photographs and license plate numbers. The plates were easy to trace: all were recently stolen from Texas or New Mexico, some within the previous few days. The stories were published, along with photographs of Mexican state police agents driving them. The stories resulted in more death threats. Two U.S. Customs agents dropped by the newspaper to warn about the threats and said they should be take seriously. “Vary your routine, and when you’re driving keep an eye on who’s behind you,” was the advice I was given.

The plot, as they say, was thickening. But how do you unravel a plot as thick as this one? How do you figure out the inner workings of collusion between crime and government? It had to have a face, but whose? Was it just the local state or federal police commander? Was a governor involved, or a powerful politician in Mexico City? So far, all I had was a vague Polaroid snapshot whose image had barely formed. It would take several more years of research before that image came through clearly.

Given the results of its reporting, the El Paso Herald-Post was in high spirits and had good reasons to be proud: A notorious drug trafficker was in jail, and a major Chihuahua police agency had been shaken to the core. Certainly, this kind of reporting did not have to end there, and it did not end there. Following the kidnapping, one of my colleagues at the Herald-Post, Joe Old, developed information regarding a suspected cocaine smuggling organization operating out of Ojinaga, Mexico, a Rio Grande town about 250 miles downriver from El Paso. The name of the drug trafficker that came up: Pablo Acosta.

Should we make Pablo Acosta the target of an investigative report?

Not much was known about Acosta other than the fact that he was a DEA fugitive who had been operating a vast crime organization from his Mexican sanctuary for at least ten years. The DEA tagged him as vicious, with little regard for human life. What made him of interest to the newspaper was the fact that American federal police suspected he had branched into large-scale cocaine smuggling. If true, this was big news. Until that time cocaine was overwhelmingly being smuggled into the United States through Florida. However, there had been recent drug busts in Alamogordo, New Mexico, and in El Paso, of two hundred and fifty pounds of cocaine hidden in the propane tanks of pickup trucks. They appeared to have originated from Mexico, not Florida. Another 500 pounds had been recently seized in Los Angeles, also in propane tanks. Were the Colombian traffickers opening up a new smuggling front? Was this Pablo Acosta of Ojinaga involved?

Because of the death threats, this was a good time for me to get out of town. I was sent on the road with a mission: to find out what I could about Pablo Acosta and his organization. I visited every courthouse in West Texas and southeastern New Mexico that had a sliver of information in court files, and I quizzed every local, state, and federal cop I could find in the hope of piecing together a bigger picture. A visit to the DEA’s divisional director in Dallas, Phil Jordan, got me an invitation to drop in on an Operation Pipeline conference in Albuquerque where I would likely find a number of people with knowledge of Pablo Acosta. I duly showed up for the banquet at the end of the conference, which had been organized by the DEA to train state law enforcement personnel about how to spot drug loads on the nation’s highways. I couldn’t attend any of the training sessions, of course, but the banquet was the key to making useful contacts.

As an attempt to develop sources, however, it was a dismal failure. Jordan introduced me to some people, and I got into some promising conversations, but the moment they found out I was a journalist, they suddenly looked up at the ceiling as if it was the most fascinating thing in the world, then slowly turned and walked away. Again and again, the same reaction. They must have learned their behavior from an instructional manual: If you encounter a journalist at a banquet, look up at the ceiling and walk away.

I ended up at a dinner table with six narcs: three DEA, three from various state narcotics agencies. I figured they weren’t likely to walk away from their dinner if they learned I was a journalist, so I made a pitch, explaining that I wanted to do a comprehensive series about Pablo Acosta and his drug smuggling operation. I explained what happened in Juarez to Gilberto Ontiveros after he kidnapped and tortured the photographer and outlined my theory that a newspaper had the clout to break the back of Mexican drug organizations if it exposed their operations and showed they operated through government patronage. The Mexican government could not afford such embarrassing publicity and would have to take action. “You guys help me out with Pablo Acosta, give me something to go on, and I can guarantee that within two months he’ll be either dead, arrested in Mexico, or turned over to American authorities at the international bridge.”

They all laughed. In fact, two of them even fell to the floor and rolled on the ground, clutching their belly. Acosta was one of the most notorious of the Mexican drug border traffickers at that time. They all knew about him and had worked cases against his people in the United States, but Acosta stayed in Mexico and nothing could be done about him. Now some border reporter comes along and says he has a way to take the guy down?

The experience fired me up all the more. I kept digging, turning up some useful information here and there. I spoke with police up and down the border, from San Diego to Brownsville, and they all had the same story to tell: Scratch below the surface of a Mexican crime group, and you will find the Mexican government is involved through one or more of its agencies. Eventually, I was able to create a profile of Acosta’s operations on the American side of the border and compile a list of 26 killings attributed to him and his drug faction, murders committed both in the United States and Mexico.

However, I was unable to get anything more than rumor and speculation that he operated with the blessing of the Mexican government. Where was the intel? Where was the smoking gun? It was clear I was not going to get any help from the DEA, the agency with all of the intel. I concluded that if I was going to get anywhere with this story, I needed to talk to the man himself. Maybe Acosta felt so secure in his position he would say something about his protected arrangement. I found a way to get a line to him and sent him a message: “They say all sorts of things about you. Would you care to give your side of the story?” He sent word back: “Come to Ojinaga, and I will talk to you.”

I was elated. This was going to be a real journalistic coup. But on the way down to the Mexican border town, I got nervous. The way the meeting was set up, I felt fairly sure about my security, but not entirely. By all accounts, Acosta was addicted to crack cocaine and chain-smoked it. In fact, part of his message to me was to ask if I would be bothered if he did drugs in my presence. I responded that I didn’t care; whatever he wanted. If he wanted to do the interview in the nude, that was fine with me. Nevertheless, I had reason for concern about his drug habit. Some of the border agents I had talked to said he was unstable. Because of his addiction, he could be charming one minute, deadly the next and with brutal flair. By some accounts, he would drag the bodies of his victims through the desert behind his Bronco until there was nothing left but a shredded torso.

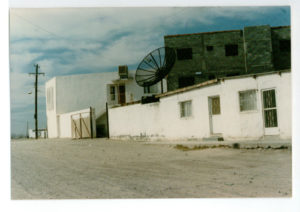

Street view of a radio station in Ojinaga owned by Malaquias Flores where the author first interviewed Pablo Acosta. Flores operated a private radio communication system for Acosta from this site. A former Ojinaga police chief, Flores became a liaison officer with the Mexican army ostensibly to handle public relations, whereas in fact he served as a go-between for the Mexican army garrison commander in Ojinaga and Acosta and played an important role in the protection the military gave the Ojinaga drug lord. (Photo by the author)

It was late October, 1986, when I got to Ojinaga. The meeting was supposed to take place at noon at Motel Ojinaga in the downtown area not far from the international bridge, but I was kept waiting for seven hours. Acosta wasn’t avoiding me, the contact person told me; he was avoiding the police. The Mexfeds had confiscated a kilogram of heroin and wanted him to pay tribute for it, but Acosta claimed it wasn’t his and was avoiding them by moving from hideout to hideout. Finally, the word came to have me brought to one of his hangouts — a radio station owned by the local Mexican military liaison. It was already dark. The streets were unpaved and bumpy, and the amber light from street lamps that filtered through the dusty air added to my surreal feeling that I wasn’t really being driven to a hideout of one of the most feared drug traffickers in northern Mexico; it was only happening in my imagination, and I should let my imagination take me back to where I really belonged, which was in my cozy, safe home back in El Paso.

Adding to the surreal was a question the driver asked me: Pablo, I was told, had obtained a large number of five-gallon glass bottles from a drug deal, and he wanted to export them to France with 20-pounds watermelons inside to sell as novelties. “Pablo wants to know: How to you put a 20-pound watermelon inside a five-gallon bottle?”

The radio station was in an adobe building with high walls surrounding a courtyard. At the back of the courtyard was a two-story building with an apartment on the upper floor. A series of metal doors led to an office. All I remember as we walked into the office was the gaunt figure of the station owner who pointed in the direction of the courtyard. When we stepped into the courtyard, I wondered if I was about to end up tied against a stake with a bunch of smugglers taking aim at my chest. I followed the contact, and as we crossed the dark courtyard, I could make out the figure of a man on the landing to the second-floor apartment. He was pacing back and forth, smoking a cigarette. Was this the drug lord himself, or one of his men?

As I went up the stairs, I scrutinized the man at the top. He was unsmiling, his face deeply lined, and he had a cigarette dangling from his lips. He was wearing a black leather vest over a dark blue cowboy shirt with pearl buttons, faded jeans, ostrich skin cowboy boots, and a belt with an oval buckle. He had stopped pacing as I started climbing the stairs, but before he stopped I noticed a .45-caliber pistol stuffed into his belt at the hollow of his back.

When I got to the top, I stuck my hand out and introduced myself. Acosta took the cigarette from his mouth and lowered his arm so that both arms were loosely at his side, like a man ready to draw his gun. He said in the gravely voice of a heavy smoker, “So, tell me. How do you put a 20-pound watermelon inside a five-gallon bottle?” I had actually given some thought to it on the way to the radio station, so I said, “There’s only one way I can think of, Pablo. You have to grow it inside.” That was the right answer. His face lit up. He threw an arm around my neck and gave me the customary abrazo, a Mexican hug that included a pat on the back while he simultaneously shook my hand. “Come in. I like talking to an intelligent man.”

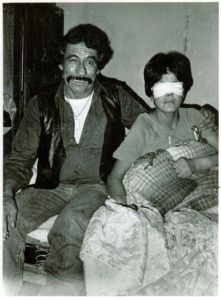

Pablo Acosta with a blind girl. He paid for surgery in an attempt to restore her eyesight, one of the good works he said he was engaged in. Photo by the author.

I spent the entire evening with him, then returned to the American side for the night and met up with him the next morning and spent most of the afternoon with him until the second hand smoke from his “cooking” a kilogram of crack at one of his hideouts made me feel nauseous, and I had to leave. The details of these two days are covered in the book, so there’s no need to go over them here, but essentially during all that time he talked about his death-defying experiences, surviving multiple assassination attempts. He obligingly went over the list of 26 murders attributed to him that I had brought with me, telling me which he did and why, and which he didn’t do, but giving a detailed explanation of those murders. During the entire time I was with him, he chain-smoked crack-laced cigarettes.

His smuggling activities and the violence associated with it amounted to color, and he was indeed a flamboyant border bandit and all-around bad guy. Anyone who has seen the movie The Three Amigos, starring Steve Martin, Chevy Chase and Martin Short, will remember the bandit named El Guapo. Pablo Acosta was El Guapo, gregarious and fond of good joke, but deadly if you crossed him or got in the way of his activities.

Just how Acosta got away with his activities in Mexico was the real story, and during my time with him I kept coming back to the question. He skirted it with a shrug, but he slipped up at one point, acknowledging that the federal police were part of his overhead. Later during the evening visit, an army officer knocked on his door. Acosta told him to come back later and explained him away as a “drinking buddy.” He denied smuggling cocaine: He was just a marijuana smuggler, nothing more, and if he had access to cocaine it was because he bought it like anyone else for his own personal use. He talked about his good works, and we wrapped up the evening by visiting a blind girl who was about to have a cornea transplant paid for by the drug lord.

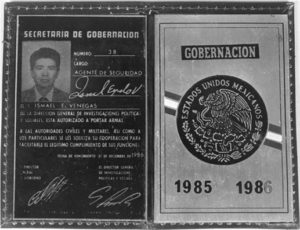

Former Culberson County (Texas) Commissioner Ismael Espudo Venegas was an important member of Pablo Acosta’s cocaine smuggling network. Though American, Espudo held the rank of federal security agent of the General Directorate of Political and Social Investigations, the political police of Gobernación — the Internal Government Ministry. The GDPSI was previously called the Directorate of Federal Security — the DFS. Such badges as the one above were carried by Pablo Acosta and other protected drug traffickers throughout Mexico, allowing them to operate with impunity. The placa, or badge, authorized them to carry weapons and instructed civil and military authorities, as well as private citizens, to cooperate “so that the bearer may carry out his legitimate duties.” (Photo courtesy of Gary Epps, U.S. Customs Service)

I had wondered what was in it for him to talk to me, and it became clear he thought he could use me for public relations. I had invited him to tell his side of the story, and he gave a version that he wanted people to believe. He had killed some people, but only in self defense; he smuggled marijuana, but did not have anything to do with cocaine. Of course, my obligation was to give two sides of the story: what U.S. law enforcement had to say, and what he had to say. The stories came out a month later in a three-part series, and they had the effect that I had predicted at the Operation Pipeline banquet in Albuquerque. The exposure blew Acosta’s relatively low profile, and his admission about federal police being part of his overhead was extremely embarrassing to the Mexican government.

Within days, Acosta was on the run and five months later he was killed after being trapped in the remote Rio Grande hamlet of Santa Elena, the village where he was born. Comandante Guillermo Gonzalez Calderoni, the federal police commander who had arrested Juarez drug trafficker Gilberto Ontiveros the year before, was ordered to take Acosta dead or alive. Acosta was given the opportunity to surrender, but he opted to die fighting.

I felt bad about it when I heard about his death, but in fact my reports merely accelerated his end. His addiction to crack cocaine had sealed his fate much more than talking to an American journalist. When I met him he was already a fading power, and traffickers even more ruthless than him were waiting behind the scenes to take over. If the Mexican government had not killed him, they would have.

Because of the drama of his death, I realized a good book could be written about him. I eventually took a leave of absence from journalism for a year and a half to research and write it. The first edition was published in 1990, with a second edition appearing in 1998. The Cinco Puntos edition was released in 2010.

Here is the essence of what I learned: Traffickers like Pablo Acosta operated under a system that was almost like a franchise. They had to pay a monthly fee to their handlers for the right to work a specific zone. It was a form of private taxation, based on the volume of sales, with the money going to people in power. Often the traffickers were given federal or state police badges, an example of which is shown on this page. The military, the attorney general of Mexico and his federal police, the Internal Government Ministry and its secret police, governors, and many other powerful people were involved. The money generated by the grunts at the base like Pablo Acosta flowed up the ladder, and much of it reached the highest levels of power, usually including the president of Mexico. I have attempted to show how this system worked through the story of the life and death of Pablo Acosta.

Everything that I learned about the Mexican system I learned the hard way, and I also learned that our own government knew about it too, but kept a lid on it. Federal agents up and down the border were told to keep their mouths shut if they valued their careers. At the time, the United States was pursuing the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Canada and Mexico, and if these truths about the Mexican government became widely known, the United States Congress would never have ratified the NAFTA agreement, which it did early in Clinton’s first term.

The people of Mexico, meanwhile, continued their arduous labor of bringing an end to the one-party system that had brought about such unfortunate consequences for the majority of Mexicans. In the year 2000, their efforts paid off with the election of an opposition candidate, Vicente Fox, as president of Mexico. The Old Regime, discredited and weakened by the well-organized opposition, did not put up a fight, but stepped back and let the election results speak for themselves.

The first six years of Mexico’s fledgling democracy were devoted to the unglamorous task of accountability — creating accounting and oversight mechanisms to protect tax money from unscrupulous politicians and bureaucrats. This corrected one of the major ills of the old order and will have long term economic benefits for Mexico. The next president, Felipe Calderon, a member of the same opposition party as Fox, then undertook the dangerous task of taking away the enormous space the old one-party regime had given to organized crime.

This has resulted in the pitting of one drug trafficking group against another and of all trafficking groups against

Get this classic book about Pablo Acosta from Amazon.com

Because of this, the survival of democracy in Mexico may actually no longer be in the hands of Mexicans. It is now in the hands of the United States government and the American people.

But that is another story.

— Terrence Poppa, 2010

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: